Helena Greter, Leader of the Competence Centre for Epidemiological Outbreak Investigations at Swiss TPH, talks about the role of the competence centre, looks at current outbreaks in Switzerland and explains why her job is more than just detective work.

What is the Competence Centre for Epidemiological Outbreak Investigations?

Since 2012, the Swiss Federal Office of Public Health (FOPH) has mandated Swiss TPH to lead the Competence Centre for Epidemiological Outbreak Investigations, short KEA (Kompetenzzentrum für epidemiologische Ausbruchsuntersuchungen). The main role of the Centre is to detect the origin of disease outbreaks such as from bacteria or viruses quickly so that effective measures can be launched timely by the responsible authorities.

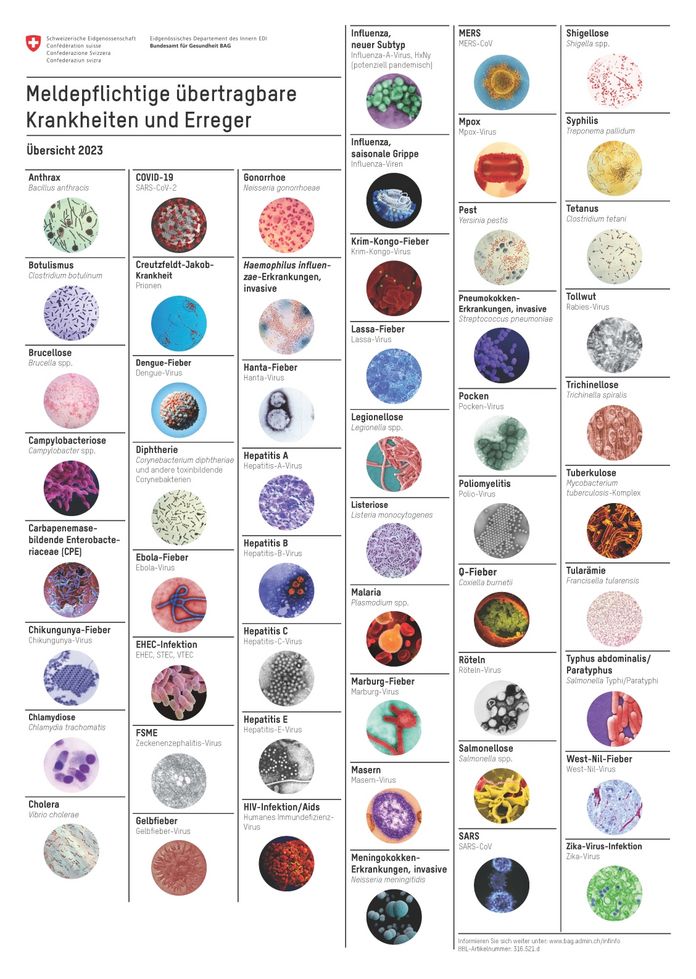

The core mandate of the Competence Centre comprises three components: First, we constantly monitor listerioris cases across Switzerland and follow up on every single case. Listeriosis is one of the deadliest food-borne bacterial infections in Switzerland, and between one and three cases are reported per week. Second, if the FOPH observes an increase in cases of one of the 54 notifiable diseases we are alerted and set up the epidemiological outbreak investigation. Most outbreaks occurring in Switzerland are caused by food-borne viruses or bacteria such as Salmonella or pathogenic E. coli. Finally, Swiss TPH also leads the development of a national digital platform for systematic epidemiological data collection and we provide our expertise to cantonal authorities on request in case of local outbreaks.

Can you explain a recent outbreak situation in Switzerland?

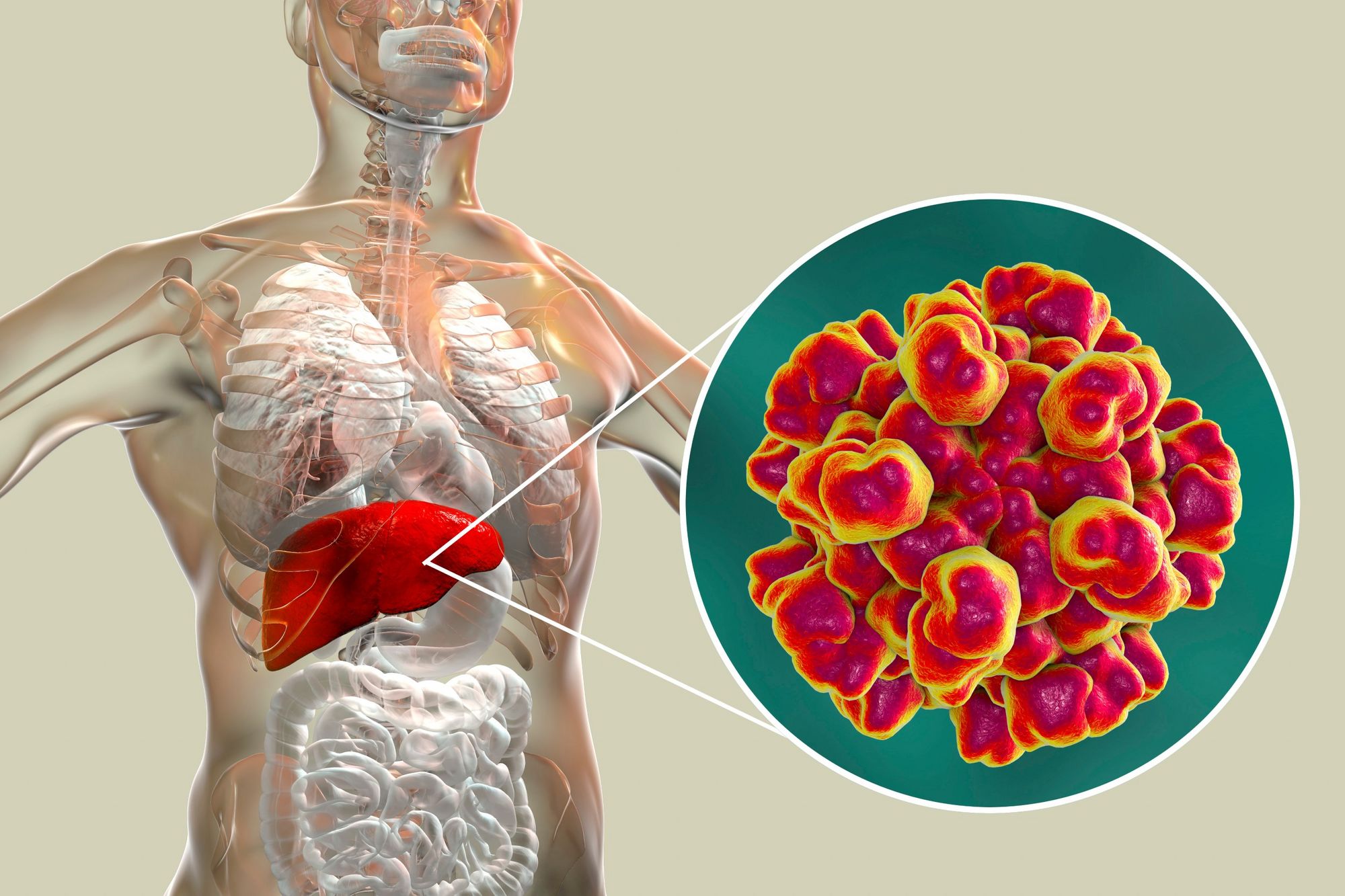

In 2021, the FOPH noticed a sharp increase in hepatitis E cases in Switzerland. Hepatitis E is caused by a virus (HEV), which leads to an inflammation of the liver. When the FOPH contacted us, there were about 80 cases reported from across the country. As we then only have 72 hours to set up the epidemiological investigation, we immediately sat together with the dedicated team at Swiss TPH to select the best fitting methodology for the study, to develop the study instruments and to allocate the human resources necessary to manage the work load. Our focus in every outbreak investigation is finding the source of the outbreak as quickly as possible. This is only possible thanks to the close collaboration within the network of the different actors such as the Swiss National Reference Centre for Enterobacteria and Listeriosis (NENT).

The study approach is selected based on the characteristics of the pathogen but also of the affected population. In the case of the hepatitis E outbreak, we knew that the source could not be travel-related but had to be linked to consumption of Swiss porc meat. This finding was shared by the Veterinary Virology Institute, University of Zurich, which performed the molecular analysis of the circulating virus and revealed that the HEV strain is of Swiss origin. We therefore decided on a case-control study, which means that we analysed not only data of the infected people (case group) but collected the same data among a healthy group of people matching the same age group and place of living as the cases (control group). This approach allows for comparing the risk behaviour of the cases and the control group, therewith revealing different patterns of exposure of diseased and healthy people.

While we prepared the study instruments, new Hepatitis E patients were being reported. All patients as well as a matched control group were enrolled as study participants and received an invitation letter including a questionnaire. Within seven weeks, we could close the study.

In this case, we could not detect a single product as the source of infection and the identified risk was rather surprising. Based on what was known about HEV in 2021, we expected the cause to be a product containing raw pork meat such as salami or mortadella di fegato. However, we found that the outbreak was rather related to the consumption of a pork meat product that was heated during production.

At the time, the standard procedure in production was to cook pork products to an internal temperature of 70 degrees Celsius for two minutes. Shortly after this outbreak in Switzerland, evidence was published that HEV is more resistant than expected and that cooking at 70 degrees may not fully eliminate the virus. In recent years, we have observed an increase in hepatitis E cases across Europe and we are continuously learning at all levels: from pork production and epidemiology to veterinary and human medicine.

What is your role in the Competence Center?

I am coordinating activities for the dedicated team at SCIH engaged in the core mandate, as well as the cross-departmental team at Swiss TPH when we conduct an outbreak investigation. I am also the single-point of contact for the FOPH, meaning that I can be contacted 24/7 in case of an outbreak. When I am on holidays, I have a deputy.

On the one hand, this is a very exciting job. On the other hand, it bears its challenges: Last year for example, there was a large Europe-wide Salmonella outbreak related to chocolate eggs only days before the Easter break: I knew I had to cancel my holidays at once.

Does your job compare to a detective’s work?

In the end, our objective is to solve a puzzle and find the needle in the haystack. So yes, in a way it compares to the work of a detective. At the same time, we still work as epidemiologist, applying standard tools such as study design and questionnaires. Even if we work under a lot of time pressure and for example continuously analyse the incoming data, we fully adhere to all scientific and ethical principles.

Also, unlike detectives, outbreak investigation requires team work across sectors and multidisciplinary collaboration. Thus, we work together with a variety of stakeholders ranging from federal and cantonal agencies to reference laboratories and beyond. In the case of the hepatitis E outbreak for example, we worked closely with the Federal Food Safety and Veterinary Office (FFSVO), the National Reference Laboratory, the Blood Donor Services, Hepatologists of the University hospitals, the Vetsuisse Faculty experts for swine medicine, and the pork producers associations, among others. It really is a key factor for success in disease control to collaborate with so many competent and engaged players across the country.

Today, you published a paper in Swiss Medical Weekly. You and your co-authors conclude that the outbreak investigation system in Switzerland “works well.” Can you explain what your findings were?

The paper reports on a listeriosis outbreak that occurred in 2022, for which we were leading the epidemiological investigation. After our team had interviewed only three cases, we identified a fish product as the source of the outbreak and after only two more interviews, we could point to the exact product. On the same day, the cantonal authorities where the production facility was located were alerted and an inspection took place, which found Listeria in smoked trout. The molecular analysis from patient and trout samples performed by NENT then confirmed that the Listeria strains were identical and hence, the outbreak could be contained very rapidly through a national recall of the concerned products as well as rigorous sanitation measures taken by the production facility.

This example showcased nicely that the multi-sectorial approach and our procedures work well. However, as pathogens evolve, we constantly need to analyse, evaluate and adapt our methodologies to ensure effective outbreak investigation in Switzerland.

Many of the pathogens, which cause disease outbreaks in Switzerland, are food-borne. Do you have any tips and tricks for handling produce properly?

A good kitchen hygiene is generally sufficient as food hygiene and control are working well in Switzerland. Some population groups are more susceptible to food-associated health risks than others including young children, elderly people, pregnant women and people with a compromised immune system. The FFSVO provides excellent and up-to-date information and guidelines on the topic: