Liz, you are currently in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) to prepare for the launch of the phase 2b trial of a new antimalarial drug. Can you tell us more about this clinical trial?

The objective of the KALUMI trial is to evaluate the safety and efficacy of KLU156. The components of KLU156, KAF156 and lumefantrine, belong to a novel class of antimalarial compounds that target both the blood and liver stages of the parasite life cycle. The compound is currently being evaluated in several countries across Africa in children down to the age of 6 months – as children under the age of five bear the greatest disease burden. This trial is conducted by Novartis in collaboration with Medicines for Malaria Venture (MMV) and the WANECAM2 Consortium, with financial support from the European & Developing Countries Clinical Trials Partnership (EDTCP).

Don’t we already have very effective and affordable medicines for malaria?

Yes, artemisinin-based combination therapies (ACTs) are still the standard of care for treating malaria and remain very effective. However, we are seeing an increase in parasite partial resistance to artemisinin.

In addition, patient adherence remains an issue particularly in low-resource settings, as many commonly used antimalarials have to be taken twice a day for three days. KLU156, on the other hand, is a single daily dose, three-day oral treatment. The formulation also differs from other antimalarials: it comes as granules in a sachet rather than a pill, which should make it easier to take, especially for children.

Tell us more about clinical trials – what exactly does it entail?

Every time you take a medicine, you rely on the trials that have been done before. When you open a pack of medicine, the information leaflet is in effect a summary of every important finding that was collected during the trials. It tells you how to take your medicine, when to take it, what side effects you might experience and what to do if you have certain pre-existing conditions.

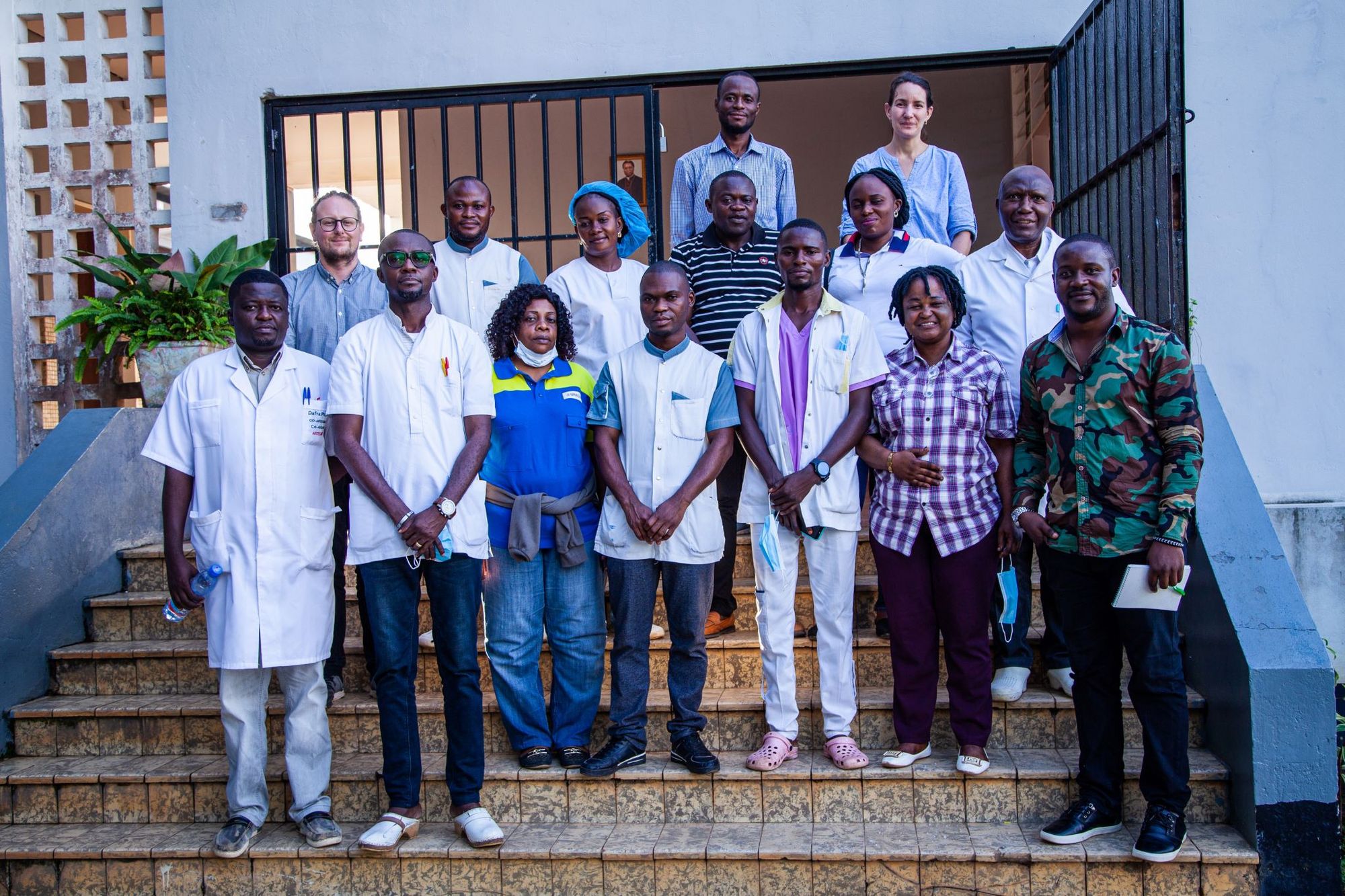

Clinical trials validate drug candidates according to very strict regulations. First, a trial must be approved by an ethics and regulatory authority, which checks that the trial is ethical and scientifically sound. On the site, all staff members are trained according to their responsibilities, starting with doctors, nurses, lab technicians, data entry staff, but also including nutritionists, cooks, etc. We cannot start a trial until the right training, equipment and conditions are in place.

There are often more than 30 staff involved for every enrolled trial participant. Everyone has to follow a very strict and ethically approved protocol. This is essential to ensure patient safety. During the trial, participants who agree to take part are followed very carefully throughout the trial and sometimes for a long time afterwards.

Is it different to conduct a clinical trial in the DRC compared to, say, Switzerland?

There is no difference in the way we conduct a clinical trial in Europe or elsewhere. However, when we test a drug for a neglected disease such as malaria, the trial can become more complex, because we have to go where the malaria patients are, i.e., to a malaria-endemic country such as the DRC.

Such sites can be more remote and are often based in resource-limited regions, so we sometimes have to build an entire clinical trial site from scratch. This involves more complex logistics such as questions around electricity, access to clean water, the hospital ward, pharmacy and laboratory, bringing in equipment and training all the staff working on the trial.

Setting up such study sites to test drugs for poverty-related diseases is something Swiss TPH has been doing for over 20 years in partnership with different organisations and countries. This is why we are a trusted partner for pharmaceutical companies such as Novartis.

What motivates you most in your work?

I am motivated in my work for both professional and personal reasons. On the professional side, it is always amazing and inspiring to work with highly competent scientists and teams. It is a privilege to be able to bring science to the bedside, to help find solutions and to keep patients and future generations safe. Clinical trials are not just about testing drugs, they are about giving hope and, especially in neglected or diseases of poverty, a better chance of survival, good health and ultimately breaking the cycle of poverty.

On a personal level, as the mother of an extremely premature baby, I am grateful to science every day because my child would not be alive today if it were not for the advances in science and the discovery and testing of certain medicines over the last 20 years. Having grown up in Africa in war-torn countries, I am intrinsically motivated to give something back and push for better access to health, science and medicines, leaving no one behind.

What other new tools are currently being developed in the fight against malaria?

What is unique about Swiss TPH is that we work all the way from basic research to drug validation and project implementation. In the field of malaria alone, I have over 200 colleagues working from understanding host-parasite interactions, developing and validating new drugs, vaccines and diagnostic tools, to vector control, intervention programmes and policy advice.

Photo credits:

Cover image: Elisabeth Reus/Swiss TPH

Portrait of Elisabeth Reus: J. Pelikan/Swiss TPH

All other images: Justin Makangara, Fairpicture/Swiss TPH