The decline of leprosy is a public health success story. However, despite being curable, the disease is still present in more than 100 countries, with 200,000 new cases diagnosed each year. Today, on World NTD Day, read about the challenges of eliminating leprosy and the work of Swiss TPH and its partners in the fight against the disease.

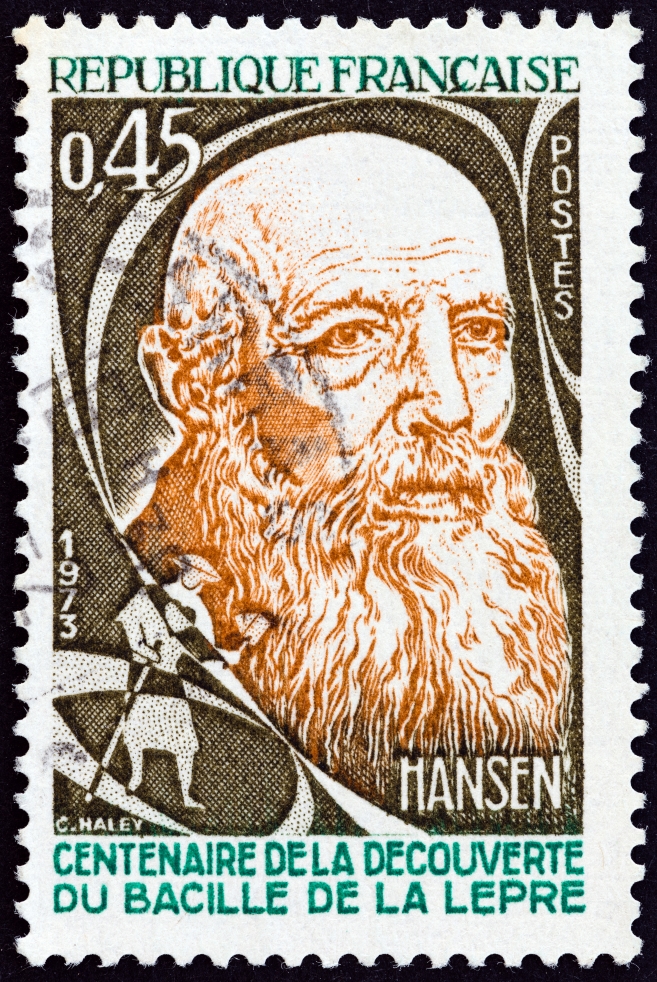

Leprosy is described in literature of ancient civilisations and also existed in Europe. It was actually in Norway that a young doctor called Gerhard Armauer Hansen discovered the bacteria Mycobacterium leprae that cause leprosy in 1873. At that time leprosy affected about 2.5 percent of the population of the city of Bergen, where he worked.

The suffering of people infected with leprosy was so acute that the disease was thought to be highly contagious. This is however a myth as today we know that leprosy does not spread easily from person to person through casual contact like shaking hands or hugging, sharing meals or sitting next to each other. It needs close and prolonged contact with a person that is infected and untreated. Moreover, 95 % of exposed people will not get infected because their immune system can fight the bacteria off. Not everything is known yet about the transmission of leprosy but the bacteria seem to be transmitted by droplets from the nose or mouth of a sick person. Once a person starts treatment, the transmission stops.

Leprosy – an NTD that comes with stigma

Today, leprosy is listed as a neglected tropical disease (NTD), even though cases still occur in countries outside of the tropics, for instance in the U.S. Globally, leprosy still occurs in over 100 countries. Around 200 000 new cases worldwide are diagnosed each year. Leprosy affects the skin, and can spread to the eyes and linings of the upper respiratory tract. As the bacteria live in nerve cells, affected parts of the body lose their sense of touch and pain, increasing the likelihood of injuries such as cuts and burns. Although it’s hard to spread and easily treatable, people affected by leprosy often face stigmatisation and discrimination.

The challenge of reaching the last mile

People with leprosy can be cured with multi-drug therapy (MDT), consisting of the three medicines dapsone, rifampicin and clofazimine. With the introduction of MDT, the global burden of leprosy was reduced by 95%, making it one of the most impressive public health stories in history. However, the number of new leprosy patients has barely changed in recent years. “The challenge is to reach the last mile to interrupt transmission”, says Peter Steinmann, public health specialist, leading the leprosy projects at Swiss TPH. “The disease is still endemic in many countries and high transmission pockets persist where it also affects children and causes disabilities, showing that it is not diagnosed at an early stage.”

Moreover, diagnosis is done by an examination of the body looking for unusual, e.g. lighter or redder patches of skin combined with nerve thickening or loss of feeling as no screening tests are available. The only confirmatory diagnostic option is to detect bacteria in skin samples under the microscope. “Additional approaches to the current standard of passive case detection are urgently needed to interrupt transmission”, says Peter Steinmann.

Large-scale clinical trials have shown that a single dose of rifampicin (SDR) given to people who have been in long-term contact with an untreated person with leprosy can reduce the risk of them developing leprosy by 50-60% over the following two years. “It is important to trace contacts, screen them and offer chemoprophylaxis to prevent the disease from spreading”, explains Steinmann.

Joining forces with the private sector and in-country partners

In 2014, Swiss TPH joined forces with Novartis Foundation and partners in Brazil, Cambodia, India, Indonesia, Myanmar, Nepal, Sri Lanka and Tanzania for the so called Leprosy Post-Exposure Prophylaxis (LPEP) programme. It was the largest ever research programme on combining contact tracing with prophylactic treatment, and in 2018 the intervention was recommended by the World Health Organisation (WHO).

The LPEP programme traced 170 000 people who had been in contact with individuals newly diagnosed with leprosy and treated 150 000 of them with single-dose rifampicin to prevent the disease. “Results of the LPEP programme have demonstrated the feasibility of integrating the intervention into routine control programmes”, says Steinmann. “This approach could massively reduce the burden of leprosy and even advance the elimination of the disease.”

To demonstrate that the interruption of M. leprae transmission through sustained health system strengthening is feasible, Swiss TPH currently works with Novartis and partners in Tanzania. “Through systematic early case detection, treatment, contact tracing and SDR post-exposure prophylaxis supported by training and systematic documentation, we want to show that interruption can be achieved in the Morogoro region, which is the region with the highest number of leprosy cases in the whole country,” explains Steinmann. “If this intervention is successful, it can be scaled up nationally and even replicated in other countries to finally get rid of this old disease.”